10 Underrated Spots to Find Shed Antlers

After you pick through the classic shed hunting spots, you should also check out these underrated honey holes

by Josh Honeycutt

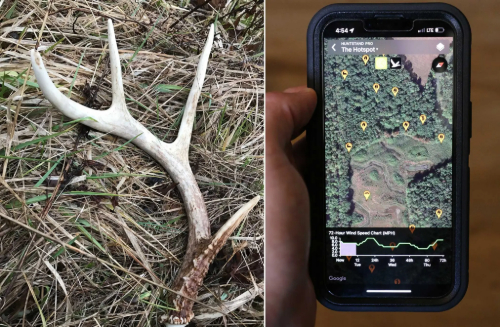

Photo by Honeycutt Creative

Shed hunting is all the rage among serious whitetail hunters these days, and rightly so. It’s a fun way to spend time in the woods and it’s a thrill to find the antler of a big buck you plan to hunt next season. But finding sheds consistently is a little more complicated than walking through bedding areas.

Of course, some shed hunting spots aren’t secrets. But others are overlooked. Here’s a list of all the high odds spots you should check on your next shed hunting trip.

The Classic Spots

Shed hunters routinely check certain areas that are proven and popular for finding antlers. For many years, shed hunters have targeted important areas proven to yield antlers. Some of the classic spots include:

General bedding areas.

Solar cover in the form of South-facing slopes.

Thermal cover in the form of dense conifers, such as cedars, spruce, and pines.

Late-season food sources, such as cut crop fields, standing crops, food plots, oak stands, etc.

Creek, river, ditch, fence, and other crossings.

Open fields, such as agricultural edges and food plots.

Underrated Spots to Find Shed Antlers

Use your scouting intel to locate more sheds. Photo by Honeycutt Creative

All of the spots listed above are excellent areas to find sheds. But after you’ve picked those classic spots over, it makes good sense to also hunt through underrated spots to find shed antlers. These are the spots that other hunters completely overlook.

1. Aging Clear-Cuts (and Other Woody Browse Hotspots)

The primary component of a whitetail’s wintertime diet isn’t ag field crops or food plots. Rather, it’s woody browse. This includes high-fiber foods in the timber and around early successional habitat. These locations provide tree buds, leaves, and key plants (think greenbriar) that deer consume to make it through winter. Many short-growing tree species, such as dogwood, provide lower branches with tree buds that are within reach.

Of course, areas with heavy logging, or even areas a few years removed (and regenerated) from a clear-cut, can provide a lot of woody browse. Because of this, expect some deer to feed here in late winter through early spring. Some sheds should be on the ground there.

2. Nasty Marsh and Swamp Islands

Deer love marshes and swamps. That’s largely due to the seclusion they provide. Oftentimes, hunters completely avoid areas if they have to cross water. If it requires knee boots, they might not traverse it. If it demands hip boots or full waders, most hunters won’t even consider it.

Whitetails recognize this and they capitalize on it. If they can find some high ground within a marsh or swamp, they’ll bed down on those islands for the daytime security provided. Only after dark will they leave these fortresses for destination food sources. That makes marsh and swamp islands perfect for finding antlers dropped during daylight hours.

3. Deadfall Timber

Oftentimes, deer choose to bed against large boulders or downed trees. The horizontal log provides them some profile cover, which can shield them visually from passing predators.

Additionally, I think that maybe these logs hold and provide some additional heat. At the very least, large logs block some winter wind. Furthermore, areas with a lot of deadfall timber tends to have an opened canopy, which promotes regrowth, effectively providing some food sources within the bedding area. (Which is a highly important feature for holding deer consistently).

4. Deep-Woods Pockets

By late winter, in areas with heavy hunting pressure, some deer retreat deeper into the big woods. If these deep-woods pockets provide food sources, such as remaining red oak acorns, woody browse, and sections of early successional habitat for food, you just might find shed antlers there. If the area offers bedding, food, and water, sheds should be there.

A match set found in a deep-woods pocket near a secluded bedding area. Derek Horner

5. Fields with Native Grasses

Laying on the cold ground with nothing but soil or maybe a few leaves does not make for a warm bed. However, native grasses tend to have hollow stems, and those retain air and warmth. (Cedar, spruce, and pine leaves/needles offer the same effect.)

There’s a reason why so many sheds are found in grassy areas. Oftentimes, it’s due to the increased warmth provided thanks to the insulated bed, which isn’t possible without that matted grass. Thus, CRP, CREP, or just a small-to moderate-sized area of volunteer grass can be a boon for finding antlers. You don’t need big fields of it, a small patch in the woods can do the trick.

6. Native Green Food Sources

OK, maybe green food sources as a whole aren’t necessarily overlooked. Green food plots, clover fields, and wheat patches are dynamite for shed hunting (and almost all shed hunters know this). That said, some green food sources certainly are less targeted. Most notably — naturally occurring green food sources.

Native green food sources, and even some invasive green food sources, can help carry deer through late winter into spring. Some of these remain green all winter long (think greenbriar). Others start greening up in late winter or early spring.

7. Out-of-the-Wind Valleys

Late winter winds are brutal, and oftentimes, these even carry into early spring. These winds cut into deer fat stores.

While thermal cover (dense stands of cedars, spruce, and pines) is the traditional method for deer to find wind cover, there is another. That is out-of-the-wind valleys. Deer can slink down into a valley between two or three properly oriented ridges and stay completely out of the wind. For example, a ridge running north-south blocks a westerly wind and a ridge running east-west blocks a northerly wind. An L- or U-shaped ridge can block most winter breezes.

8. Sanctuary Edges

I’m not talking bedding areas, or designated private-land sanctuaries. Rather, some hunters find their hunting areas border sanctuary properties that are either highly managed or allow no hunting at all. Because of this, by late winter, deer often retreat to such areas. Of course, you can’t shed hunt those properties without permission from the landowner. That said, it’d be a poor decision not to walk your side of such boundaries. Some deer will cross over to your side, even if only briefly, and some might drop antlers while doing so.

9. Travel Corridors

Deer sometimes travel long distances to get from point A to B. Some of these travel corridors are used daily. Others are used less often. Maybe they’re moving from bedding to feeding. Perhaps a pack of coyotes push through and bump them from one farm to another. Whatever the case, deer tend to use familiar travel corridors.

Because of this, even areas that are just open fields between pockets of good whitetail habitat, or a stand of mature timber that’s largely useless at this time, might provide medium- to long-range travel routes. Sometimes, deer shed while traveling these, even if they don’t use them daily.

10. Supplemental Feeding Stations

Although not legal everywhere, one of the best and most underutilized tools for shed antler hunting is a consistent supplemental feed station. Most hunters that can legally bait or feed do so during deer season, and then promptly quit upon closing day. From a general land management and shed hunting perspective, that’s a mistake.

Over time, deer remember where these feeding stations are located. Even if they don’t have historical knowledge of these, deer are adept at finding food quickly. So, if you fed during deer season, and it’s legal to continue doing so, provide supplement feed as long as state agencies allow it. That’s sure to boost your shed totals each spring.

Shed hunt in overlooked areas to find antlers others don’t. Photo by Honeycutt Creative

Final Thoughts on Shed Hunting

Shed hunting is an excellent way to learn more about your hunting areas and the deer you might be targeting. Of course, hit those traditional shed hunting hotspots noted above. But also factor in the overlooked shed hunting spots we covered here.

Then, use good shed hunting tactics to haul in those cast crowns. Remember, you’ll find more antlers by moving at slower paces, and in slower places, such these overlooked locations.