Funky fish: Gar garners protections from Minnesota lawmakers

by Associated Press

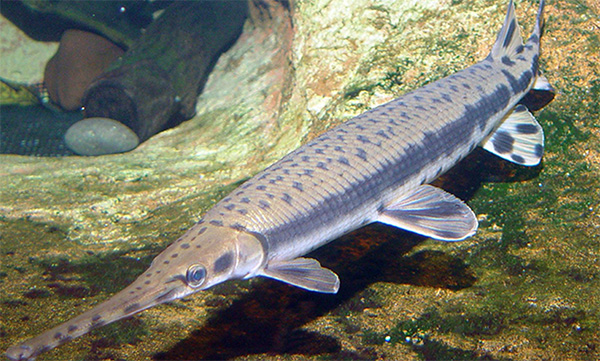

ST. PAUL, Minn. — One of Minnesota’s oddest, perhaps coolest, and definitely historically underappreciated fish – the gar – is about to get some love.

The long, slender, toothy and prehistoric-looking fish will, for the first time ever in the state, be protected in ways similar to other gamefish, the result of a bit of an outcry on social media following a series of mass killings that some saw as wantonly wasteful. In a legislature divided starkly along partisan lines, Minnesota’s gar species found bipartisan support.

Officials say they aren’t sure exactly what restrictions they’ll place on catching and killing gar, but the move carries a growing awareness of changing attitudes toward native fish that humbly live on the opposite end of the piscatorial spectrum from celebrated fish like walleye and bass, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported.

The much-larger environment and natural resources bill approved by both the House and Senate and contains one brief reference to gar: “The commissioner must annually establish daily and possession limits for gar.”

That simple sentence has gar advocates – and yes, there are a few _ celebrating.

“This is a fantastic move for conservation of these underappreciated species,” said Solomon David, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Nicholls State University in Louisiana. More on point: David is a gar researcher and ambassador, having done his dissertation on gars of the Great Lakes region, and is the principal investigator at the university’s Gar Lab.

“Most states don’t have anything for gar,” he said.

It’s true. Most states, including Minnesota, consider any gar, which are native to North America, as a “rough fish” with no limits for how many you can kill, of any size, any time of year. It’s a legacy of the ignorance of European-centric thinking when America was settled and at various times has applied to native trout and muskellunge – vaunted species today.

Today’s Minnesota rough fish include suckers, bowfin, the native carp-looking (but not a carp) buffalo, and freshwater drum, as well as gars. Such fish have virtually zero protection from being killed, be it by hook and line, archery or pitchfork-looking spears through the ice.

Two species of gars (some say “gar” is the plural, and the rules have waivered) are native to Minnesota, the longnose gar and shortnose gar. They slide along the backwaters of the large river systems and for years haven’t gained much attention. Anglers occasionally catch them, but their bony mouths tend to resist hooks. A small subculture of fly anglers target them with essentially tassels of yarn that get tangled in their teeth.

The larger of the two, the longnose, can live for up to 40 years; the official state record, caught in the St. Croix River in Washington County, measured an impressive 53 inches, weighing in at a slender 16 pounds, 12 ounces.

Brad Parsons, director of fisheries for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, acknowledges the agency isn’t exactly sure how healthy gar populations are in the state.

“We assume so, but we honestly don’t know,” Parsons said. Still, the idea of any native fish being regulated as if it has no value has always irked Parsons, a veteran fisheries biologist who spent decades studying the tapestry of native fishes in the upper Mississippi River in Minnesota.

“These are really cool fish,” he said. “At the DNR’s pond at the State Fair, it’s the paddlefish and longnose gar that get the most attention.”

When he took over the DNR’s Fisheries Division several years ago, he began a slow campaign to change things. This year’s fishing regulations contains a half-page section urging anglers to show rough fish some respect.

The eelpout, or burbot, recently was taken off the rough fish list and declared a game fish, much to Parsons’ pleasure.

But the DNR had nothing to do with starting the new gar protections.

That began as a backlash to a video posted to YouTube by some Minnesota ice fishermen who were spearing gar through large holes in the ice _ a legal pastime called “darkhouse spearing” that is generally practiced for northern pike, but also legal for rough fish and harmful invasive species.

The video, which has since been removed from YouTube, showed 82 dead gar laid across the ice. The spearers said modern technology, including sonar, helped them target the fish. The incident caused an outcry _ especially because law enforcement officials determined that the massacre was legal because the fish were not literally discarded, but used in some fashion, likely donated for fertilizer, as is done with non-native common carp.

Similar incidents have garnered backlash elsewhere, including Oklahoma bowfishermen killing and throwing overboard more than 1,000 gar in one outing. It’s the flip side of publicly posting wildlife exploits on publicly viewable websites.

David has been one of those raising a stink.

“These are native apex predators that serve a great role in our ecosystem,” he said in a recent interview. “Instead of of pitching them in a field and justifying it as fertilizer, we should view these fish in the context of other predators.”

For example, David said that, while this hasn’t been established, it’s possible that gar could prove valuable in controlling invasive carp marching up the Mississippi River because gar often favor shallow backwaters, even when oxygen is low, and could be the only predator of young carp in such waters.

The situation caught the attention of some lawmakers and Rep. Jamie Becker-Finn, DFL-Roseville, introduced the measure.

Initially, several Democratic lawmakers wanted to take it further, classifying gar as a gamefish, but that idea lacked enough Republican support to advance. The comprise that resulted will require that the DNR set daily and possession limits for gars – a move that, practically speaking, allows them to be as protected as game fish.

Parsons said even though the DNR had nothing to do with the initiative, the DNR is more than happy to do that. He said the next task is to talk with researchers, gar anglers and other interested parties to try to figure out what those limits should be.

“We really haven’t gotten into it yet,” Parsons said. “I would doubt there would be closed seasons, but we absolutely could see some limits.”

Wisconsin pioneer remembered amid women’s fly-fishing boom

by Associated Press

MADISON, Wis. — Traditionally seen as a man’s sport, fly-fishing has grown in popularity among women and girls over the past few years, and women are its largest growing demographic.

Jen Ripple, editor-in-chief of DUN Magazine, an international women’s fly-fishing magazine, said that could be for several reasons, but particularly because the sport has become much more affordable and women are encouraged by seeing each other try it.

“If they see someone that is just an everyday woman who has picked up a fly rod and had a great time … that’s something women look at and say, ‘Hey, maybe this is an activity that I can do with my friends with my family,'” she said.

“The difference is that in a conventional fishing state, you are using a lure that is weighted,” said Ripple, a professional fly angler and fly-fishing educator. “Our flies don’t weight anything, so the way that we get our fly to our target is through a weighted line.”

Despite being male-dominated, fly-fishing has a rich history of involving women, Wisconsin Public Radio reported.

Carrie Frost was a female fly angler and pioneer who used her experience in fly-fishing to establish her own business that employed mostly women in Stevens Point.

Ripple said Frost, who was born in 1868, found success in part because of her focus on the local environment. She made flies with local feathers and furs to mimic local insects. At the time, flies were brought in primarily from Europe.

“She also tied flies that look like the bugs that were in her area,” Ripple said. “And I think that’s a super important part because flies in the English waters did not always compare in color and size to what she was seeing in Wisconsin.”

But even prior to Frost, as far back as the 15th century, some historians believe the first book about fly-fishing was written by a nun born of nobility, Dame Juliana Berners, who wrote “Treatyse of fysshynge wyth an Angle” or “Treatise of Fishing with an Angle,” that touched on everything from dying horse hair for different water conditions to conservatism.

Although she’s from a family of anglers, Ripple didn’t fall in love with the sport right away. It took her signing up for a fly tying class in Michigan before it really became a passion.

Ripple said the sport is also accessible to young children, pointing to Maxine McCormick, a teenager who many believe to be the best caster in the world.

“Fly-fishing has absolutely nothing to do with strength, which makes it perfect for young and old women and men alike,” she said.

And, she said for fathers and male caregivers, it’s important to pay attention to cues from their children, and especially daughters, showing interest in the sport.

“I think a lot of fathers overlook the fact that their daughters might want to try this,” she said.

Minnesota 112-year-old bigmouth buffalo oldest age-validated freshwater fish

By Outdoors News Staff

A 112-year old bigmouth buffalo from Minnesota blew maximum age estimates for the species out of the water, so much so that the bigmouth buffalo became the oldest age-validated freshwater fish.

The supercentenarian fish was collected as part of a North Dakota State University study, and more than quadrupled a previous maximum age estimate of 26 years. That estimate was based on an Oklahoma State University analysis of six bigmouth buffalo collected in the Keystone Reservoir near Sand Springs in 1998. The OSU team shared its findings in a paper titled “New Maximum Age of Bigmouth Buffalo,” but the authors also included their belief that many bigmouth buffalo populations may have fish older than 20 years, the maximum age estimate prior to their study.

In this more recent study, the North Dakota State University team collected and aged 386 bigmouth buffalo from Minnesota waters from 2016 – 2018. Ages of those fish, including the 112-year old individual, were determined by a count of the annual growth bands on one of the fish’s three pairs of otoliths, or earstones. In addition, 28 otolith samples were used to test whether the otolith annulus counts were accurate. This was done via bomb radiocarbon dating, a particular type of carbon-14 dating. The presumed otolith annulus counts were indeed thoroughly accurate, as they were validated not only cross-sectionally among individuals, but also longitudinally within individuals. The five oldest fish in the study were all more than 100 years old, and many of the populations studied are dominated by fish more than 80 years old.

The study’s authors also had a hunch that bigmouth buffalo develop black and orange markings as they age. So, in addition to examining the fish’s earstones, the North Dakota State University team also looked at individual fish’s body markings to see if pigmentation could give clues about the fish’s age. Of the study’s fish, the markings were almost never found on fish younger than 32, yet were almost always present on fish older than 45. Black markings are thought to be obtained from sun exposure over time, and orange spots are thought to result from the fish’s diet, both environmental factors that can be influenced by water quality.

Finally, the North Dakota State University team estimated the reproductive maturity of bigmouth buffalo. Forty-four of the study’s fish were examined for this objective; 14 were male while 30 were female. The onset of sexual maturity was estimated at 5 – 6 years for males and 8 – 9 years for females, but may have been underestimated for females. This finding contradicts previous studies of the species that indicated bigmouth buffalo may reach maturity as early as the first year of growth.

Not only does this study shatter our perceptions of bigmouth buffalo longevity, it also shows that the fish mature at a later age than previously thought, and suggests that age classes may not reproduce each year. Another study in North Dakota confirmed that bigmouth buffalo exhibit what is called “episodic” or irregular recruitment, and that it is related to environmental conditions. The fish have occasional years of spawning success separated by periods of poor reproduction for a decade or more. They also found that in North Dakota, the onset of sexual maturity is 6 years for males and 10 years for females. As a large-bodied and long-lived species with few natural predators, this slow-paced life history strategy is considered a suitable one. The new life history information on bigmouth buffalo, and similar data specific to Oklahoma, can help biologists better understand and collect further data to manage this species, and other species like it, in Oklahoma.

2019 was a big year for buffalo news. Three weeks before the North Dakota State University study was published in late May 2019, an Oklahoma angler caught his own record-breaking buffalo. Hugh M. Newman caught a 66-pound female smallmouth buffalo from Broken Bow Reservoir. This new Oklahoma record was estimated to be 62 years old, and is thought to be the oldest reported smallmouth buffalo.

— The Fishing Wire

In Montana, breaking the 18-pound walleye barrier

By Outdoors News Staff

Montana anglers have landed six new state record fish since last August. On May 10, Trevor Johnson of Helena added a seventh whopper to that list when he reeled in a huge walleye from Holter Lake near Helena.

Johnson’s fish weighed in at 18.02 pounds on a certified scale, measured 32.25 inches in length, and 22 inches in girth. He caught the record-setting fish on a jig. The previous state walleye record was set in 2007 with a 17.75-pound fish from Tiber Reservoir. For more on the record catch, click here.

Other recent state record fish include a chinook salmon caught last August, a smallmouth bass in October, a yellow bullhead in December, a brown trout in February, a longnose sucker in March, and a largemouth bass in April.

Lake Erie yields another jumbo – as in a Pennsylvania record perch

By Outdoors News Staff

HARRISBURG, Pa. — Pennsylvania has a new state yellow perch record, according to the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.

On the afternoon of April 9, angler Kirk Rudzinski, 63, of Erie, departed the East Avenue Boat Launch along with friend Sam Troup, 62, also of Erie, to enjoy a few hours of fishing on Lake Erie. The friends traveled four to five miles east to the area of the Sunoco Cribs where they anchored in sight of the high-rise building at the Brevillier Village community.

Rudzinski was targeting yellow perch using live emerald shiners as bait on a casting rod fitted with 10-pound test braided line with an 8-pound monofilament leader and a pair of size 4 hooks.

“We had been catching them pretty good throughout the afternoon, but then the school of fish moved and so did we,” said Rudzinski. “We pulled anchor and moved about a hundred yards east where there were some other boats and we started to mark fish again. We noticed there was a really strong current on the bottom of the lake that day, so we had to cast into the current.”

The technique seemed to work, and at approximately 7:21 p.m., Rudzinski felt the bite of a lifetime.

“When I felt the pull, I thought for sure that I had a double,” recalled Rudzinski. “My drag was set pretty loose and as I was reeling, the fish was taking some line. As it got closer the boat, I realized that it was a single fish and I told Sam he’d better grab the net!”

Rudzinski says the large perch was securely hooked in the upper lip, and after a two-minute fight, Troup netted the fish and brought it aboard the boat. Rudzinski says he knew right away the fish was the largest he’d ever caught.

“Oh, my gosh! This has to be a state record,” Rudzinski recalls saying at the time of the catch. “I’ve been fishing on Lake Erie for 45 years and I just love fishing for yellow perch, so I’ve seen a lot of them. Then I saw a few eggs start to drop out of the fish, and I worried that if it was a potential state record, it was going to be losing weight quickly.”

Rudzinski says a scale aboard his boat malfunctioned, so he didn’t immediately know the true weight of the fish. While he considered ending the fishing trip immediately to take the fish to a certified scale, he and Troup decided to put the fish on ice while they continued to fish until sunset. At approximately 9:15 p.m., Rudzinski and Troup arrived at East End Angler, a bait and tackle shop owned by Rudzinski, which also has a certified scale.

The scale weight of the Yellow Perch was 2.98lbs. In accordance with PFBC State Record Fish Application Rules, the weight is rounded up to the nearest ounce, making the weight 3 pounds, 0 ounces, exceeding the current state record by two ounces. The length of the fish was 16-7/8 inches, with a girth of 14 inches. State record fish are judged only by weight and must exceed the previous state record by at least two ounces. The previous state record yellow perch caught in Presque Isle Bay in 2016 weighed 2 pounds, 14 ounces and was also caught by an angler from Erie County.

Rudzinsky kept the fish on ice until the following day, when PFBC Waterways Conservation Officer Matthew Visosky arrived at East End Angler to verify the species, weight, and review photographs that were taken throughout the initial weigh-in. In addition to a witnessed weigh-in and PFBC in-person inspection, Rudzinski completed an official state record fish application including color photographs, which was reviewed by PFBC Fisheries and Law Enforcement officials and confirmed.

“It’s a thrill to know that there are big fish like this out there,” said Rudzinski. “Walleye fishing has been world-class on Lake Erie for several years now, but the Yellow Perch fishing has been a challenge. We’re in a bit of a decline. It’s not only a thrill to have this record, but this big fish is a really positive sign of good things to come.”

Rudzinski plans to have the fish commemorated through taxidermy and will display the mount at East End Angler for the enjoyment of others.

— Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission