Winterizing Your Outboard

How To, On The Water

by Louisa Beckett for Mercury Marine

Should you do it yourself or take it to a shop?

When the frost is on the pumpkin, it’s time to prepare your outboard engine(s) for its “long winter’s nap.” It may be tempting just to throw a cover over it and call it a day, but temperatures below freezing can cause costly damage to an engine that isn’t winterized properly in the North. Whether you do the job yourself or take your outboard in for service, spending a little time and money today potentially can save a lot of both come spring.

Why go to a pro?

“The new engines are quite sophisticated and on some of them, the spark plugs can be hard to get to,” says Scott Klein, president of Wendt's Marine, an award-winning marine service shop in Van Dyne, Wisc. He’s seen what can happen when a DIY’er pulls the spark plugs out of an engine to spray fogging oil or engine oil into the holes, then cross-threads the plugs trying to put them back in. As a result, he says, “The hole is shot and you have to change the head of the engine, which costs about $1,000.”

In addition, Klein says, “When we are running the engines, we might see things that are wrong with them that our customers might not catch. It will cost you a couple of hundred bucks for winterization here, but you might be saving thousands.”

It also can pay to shop around for a marine service center or marina that offers a “bundle deal” – for example, if you winterize your boat and engine with them, they may give you a break on storing the boat or even shrink-wrap it at a discounted price.

If you decide to go the DIY route with winterization, however, as many outboard owners do, start with your boat and engine on the trailer or remove the outboard and bolt it to a workbench. It will save time to be sure in advance that you have all the tools, hoses, drip pans, and winterizing products you’ll need for the project.

Fill the fuel tank. Putting fresh fuel in the boat’s tank and treating it with marine fuel additives will help the fuel system sit idle until spring without any problems. If you leave the fuel untreated, some of its components inevitably will begin to oxidize and form a gum-like substance. In the spring, when you try to burn this fuel, it can leave deposits in your engine’s combustion chamber, and over time these deposits will build up and reduce the engine’s performance.

“Most of the issues our dealers run into are caused by stale fuel,” says Mercury Technical Service Department Team Leader Ryan Russell. “If the fuel in your tank is more than a month old, pump it out and replace it with fresh fuel.”

As you drain the fuel tank and line, also drain the fuel from your engine, keeping the spent fuel to discard properly (another possible reason to let a service shop do the winterizing for you). After draining the engine, replace the fuel filter so it will be clean and ready to go in the spring.

If possible, refill the tank with ethanol-free fuel such as REC-90, a premium blend formulated specifically for recreational engines. Due to the widespread controversy over the negative impact that ethanol-treated gasoline can have on marine engines, REC-90 is now available at more gas stations in the U.S. and Canada. Stop when the tank is about 95 percent full, because extreme temperature changes over the winter can cause the fuel to expand, potentially forcing gas out of the engine’s overflow vents.

Treat the fuel. “The best time to treat fuel is when you pump it into your tank, either during your last fill-up of the season or when you replace stale fuel during winterization,” Russell says. He recommends using the Mercury fuel care system, which includes Quickare, Quickleen and Quickstor, whether your engine was built by Mercury or another manufacturer. These products are engineered to work together to optimize fuel, remove any leftover deposits from the engine, and protect the fuel system over the winter months.

If your outboard is a four-stroke, after you treat the fuel you should change the oil and oil filter before you run the engine. The goal is to have the whole engine clean and ready to go in the spring.

Next, run the treated fuel through the fuel system for 10-15 minutes to ensure it penetrates every component.

Fog the engine. Now that the motor is warmed up, remove the spark plugs and spray 1 oz. of fogging oil (for four-strokes and conventional two-strokes) into the inside of the engine to prevent corrosion. Look for fogging oil that’s specially designed for use during winterization, such as Quicksilver Storage Seal. With direct-injected engines such as Mercury OptiMax, use 1 ounce of DFI engine oil instead of fogging oil. A small oil can with a long flexible neck works best to inject the oil into the cylinders for this application.

Russell also recommends putting a coat of anti-seize lubricant on the plugs’ threads before (carefully) replacing them.

Change the gear lube. Check your engine’s lower unit for water; if you find water, be sure to drain it. Water can freeze and expand during storage, potentially cracking the unit. The next step is to change the gear lube and replace it with fresh lube, along with new washers on the fill and vent screws. As you drain the old oil, inspect it carefully. “If it’s milky, it indicates a leak. Take your outboard to the dealer for service,” Russell recommends.

“If we see it run milky, we know you might have a seal out somewhere,” Klein agrees.

“Take care of it in the fall; don’t wait ’til spring,” adds Russell.

Check the prop shaft. With some gearcases, you will have to remove the propeller in order to change the lube; but even if your engine doesn’t require that, it’s a good idea to pull the prop off anyway. Inspect it for damage and send it to be repaired if necessary. This also is an ideal time to check the shaft for debris and fishing line that might be wrapped around it, which could spoil your whole day at the start of next season. If the prop is okay, either replace it or store it separately from the engine to discourage thieves.

Check the trim fluid. You will need to tilt the engine all the way up to get to the pump. The fluid inside should be bright red; if so, check the level and top it off it it’s low. If the fluid is pink or milky, indicating the presence of water, drain it and replace it, then take your engine to the dealer for service.

Lubricate any grease points. These can vary from engine to engine. Consult your Owner’s Manual to see where your outboard needs grease.

Touch up any nicks or scratches. Inspect your engine’s lower unit and repaint any wear-and-tear marks with paint from your touch-up kit or matching marine paint.

Check the battery. If it’s a lead acid battery, inspect the fluid level and add distilled water if needed. Be sure the battery is fully charged, remove it from the boat, and store it in a cool, dry place.

Store the engine upright. At that angle, it’s easier for your outboard’s self-draining system to work all winter. Cover the engine to protect it from the elements. Make sure you rig a prop inside to hold the cover up. “I’ve seen the weight of the snow break a boat’s windshield,” says Klein.

He also advises putting a dryer sheet into your outboard’s engine cowling to prevent tiny mice from climbing in and chewing the wires. “Mice don’t like dryer sheets,” he says. “You just have to remember to get it back out in the spring.”

What if you are impervious to the cold and plan to use your boat for fishing until mid-winter the ice freezes solid on the lake? Klein has customers who do that, especially when the winters are mild. Don’t forget, he says: “You still have to do maintenance to your outboard and change the oil.”

Follow these tips and in the spring you’ll be back out on the lake casting for fish while some of the other anglers are still turning a wrench or taking their outboards to the shop.

Why the hot summer bite is the perfect time to try something new

Now’s the time to bust out those new, never-used lures

By Gordy Pyzer

Most fishing how-to articles focus on ways to counter tough conditions so you can at least scratch out a few bites. But what about those rare days when the stars align and the fish—whichever species you’re after—can’t lay off your bait? Do you just sit back and enjoy the moment, or do you try to squeeze even more success out of the situation?

If only we could predict with certainty those few times each summer when the bite is going to explode. Well, actually, you can indeed forecast with amazing accuracy when you need to drop everything and pick up your fishing rods—if you know what to look for, and what to do.

Watch the weather

The key to a hot bite is a long string of uninterrupted days—the longer the better—when the air temperature and relative humidity are steadily increasing. You’ll find the fishing gets better every day these favourable conditions persist, but the high point will be when the weather report says a massive thunderstorm is rolling your way, bringing with it some relief from the oppressive heat and humidity. Trust me on this, because it will only happen a handful of times during the summer: Go fishing immediately prior to the storm arriving and you’ll knock the ball out of the park. That alone is information worth knowing, but you can double the rewards if you try two things that seem totally counterintuitive.

Fish different water

First, leave your favourite honey hole, even when you’re catching fish. Just before the storm arrives is the time to check out those structure and cover options you’ve always suspected of holding fish, but have never tried. This is the quickest way you can confirm, once and for all, that a good-looking spot is, in fact, a good spot.

Similarly, just before the storm hits is also the time to leave behind the hot lake, river, reservoir, pit or pond where the fish are biting feverishly and test that new water you’ve always wanted to explore. That’s what I did a couple of summers ago when my grandson Liam proclaimed he wanted to catch his first muskie. In that case, I waited until the mid-July temperatures were scorching and the humidity was so stifling we were dripping with sweat as we hitched the boat to the truck.

Our destination was a small backcountry lake I’d never fished before, and I was certain we were going to have fun because the forecast called for a massive thunderstorm later in the afternoon. When the sheets of rain finally descended, Liam and I didn’t much care—we were already on the way home after boating several big toothy critters. Not bad for a 13-year-old kid on his first muskie mission.

Try new presentations

Even if you aren’t willing to leave your favourite hot spot when a big storm is in the offing, you can still take advantage of the situation to try something different. Now’s the time to take off that trusted bait you’ve always relied on and instead cycle through the various lures and techniques you’ve read or heard about and always wanted to try.

It never ceases to amaze me how anglers will routinely make an effort to learn a new presentation at precisely the wrong time—namely, when they’re having difficulty finding fish and none of their usual tricks are working. The problem is, they’re bound to get the same meagre results and learn little.

Instead, the trick is to experiment with a new technique when the action is fast and furious. Whether it’s trolling a slow-death rig for walleye, casting chatterbaits for largemouth bass or pitching swimbaits for lake trout, you’ll often discover the new presentation is even better than your faithful favourite. And in the process of catching fish, your confidence will soar sky-high.

Going on a backcountry fly-fishing trip? Here’s how to prepare

Pack mentality

For a successful backcountry trip, the right gear is essential

By Scott Gardner

The pleasures of a remote fly-fishing trip are many, including pristine waters, cooperative and plentiful fish, and good company (or no company at all, if that’s your thing). But there are also challenges, especially if your tackle is limited to what you can reasonably carry, canoe or fly with. I’ve been on many backcountry fly-fishing trips, and on the early ones, well, let’s just say mistakes were made. But thanks to my obsessive habit of making packing lists and reviewing them after every trip, as well as archiving them on Google Docs, my planning process has gotten pretty refined. Here are a few of my tips.

Research:

No aspect of backcountry prep is more important than research. At a minimum, you need to determine the species and size of fish you’re likely to encounter, whether you’re fishing rivers, small lakes or big lakes, and the modes of travel. It’s also helpful to know if you’ll be fishing from shore, wading or casting from a boat, and what size of boat. These factors will help you choose the right rods, reels, lines, flies and accessories, including the always-vexing question whether you need to bring waders. This may seem like kindergarten-level stuff, but over the years, I’ve seen some woefully sloppy preparation—the most dramatic example was a trio of Colorado anglers who arrived at a pike lodge with only trout outfits and 20-pound mono for bite tippets.

Tackle:

I always bring multiple fly rods, and I keep them in cases during transport, including portages. Fly rods are just too easy to break, especially the delicate tips, thanks to screen doors, stumps along the trail, getting stepped on and, once in a while, big fish. If you don’t have a backup rod, borrow one or buy an extra rod and sell it after the trip. It’s that important.

Floating lines are always essential, but also bring sinking lines because they open up a lot of fishing options, especially if you’re sharing a boat with spin anglers who might want to target deeper water. If you don’t have space for spare reel spools, at least bring some sinking leaders, which easily fit in your pocket.

Finally, you can never overdo it with leaders and tippet material. I always bring at least two spools of every pound test I need. If I have enough tippet to tie leaders for everyone in camp, for twice as long as I plan to be there, I feel I’ve brought enough.

Flies:

Backcountry fish are rarely fussy about fly patterns. If you get an edible-looking, appropriately sized fly in front of them, they’re likely to bite. I always stock a couple of fly boxes with a small variety of generally imitative patterns in basic dark, light and bright colours, in a range of sizes. I also bring extra flies in sealable bags to resupply my boxes as needed. That reduces bulk, and if you lose a fly box, you still have extras safely stored elsewhere.

Accessories:

Fly anglers tend to walk around festooned with accessories, but there are a few extra essentials you need in the bush, including a tip-top repair kit (though intended for spin gear, they will do on a fly rod), superglue, spare polarized shades, fingerless wool gloves for handling line on cold days and, of course, Buff-type neckwear to look cool in photos. And if you’re going to a lodge or outpost, check with the outfitter before packing bulky items such as waders, a landing net or a PFD, since those may be supplied.

Finally, here’s a packing trick my fishing buddy Jacob Sotak (pictured above) learned when he was a staff sergeant in the U.S. Army: Lay out all your gear in one place and check each item off your list as you actually pack it. That way, you avoid the dreaded “Darn, I was sure I packed that” as you desperately comb through your bags when gearing up at camp.

Bonus tip: Gear fear

Never take new gear into the backcountry without, at the very least, testing it beforehand. Deep in the woods is a bad place to discover your flashy new fly reel doesn’t actually fit on your rod or your wading boots are too small.

Panfish continually rank as one of the most commonly targeted species in the U.S., and in northern waters, their popularity exceeds that of even largemouth and smallmouth bass. If panfish are popular, then crappies are the undisputed heavyweight champion of the group. They have become increasingly sought after nationwide as new people are introduced to the fun and table-fare they provide. Their appeal is simple, especially in spring as their availability is widespread, and they are attainable by anglers of many means, ages, and skill-levels.

Fishing for crappies can be basic yet enjoyable as they fill spawning grounds in the shallows and provide some excellent angling well into the late spring period. That said, there are some details that will make certain anglers more successful than others, and those specifics relate heavily to what seasonal movements and weather does to affect everything from their location to the presentations we use.

Weather and the Cold-Water Effect

Generally speaking, most spring weather patterns are highly variable as morning moisture evaporates and takes shape as clouds across our lakes areas. Rain and wind events can settle in for days at a time, also providing a great deal of dynamic change for spring crappies carrying out their spring rituals. With that said, water temperature is a primary variable and bellwether to movements and the bite.

Early on, just after ice out in northern lakes and as water warms south of the ice-belt, the cold-water effect lingers with overall diminished crappie activity in morning, and a later afternoon flurry as water temps climb 5 degrees or more in the shallows within the same day. Increased sun angle gives way to more actively biting fish the longer that the sun shines onto rocks, sand, or shallow black-bottom bays, thus driving fish closer and closer to the shallow water spawning grounds they traditionally utilize.

Depending on your neck of the woods and how the spring season shapes up, crappies will usually stage to spawn and dump eggs in that 55-65 degree water temperature range. That said, anytime water temps stabilize and maintain consistent 50 degree temps, you can expect to find crappies roaming the shallows in good numbers.

Location, location, location

Water temperatures are the primary driver of spawning (and catching) locations, as fish favor those areas that warm first and hold that temperature well, but to find crappies consistently, a little knowledge from the winter seasons can go a long way. I start with mid-winter community holes that anglers frequent to find schooled up groups of crappies over depth. These areas can be in 50FOW or more, but in most instances, you can draw a nearly straight line from these holes, to pre-spawn staging areas, and the eventual spawning shallows. Think of this line as a continuum of depth from which to search along. Start deeper, and move to shallower staging areas like a weedline or edge of a flat in 10-12FOW, then move all the way up to the shallows beyond, shallower than 6-8FOW.

The best areas have a well-defined basin, that gives way to an inside turn or “chute” that fish follow back and forth as water temperatures and weather changes. Animals of all kinds are well known for using topographic funnels and land contours for movement, and fish are no exception. Underwater topography concentrates movement, making inside turns and the inward directions that point towards the shallows great locations to start.

On cooler, overcast or rainy days within the spring period, consider following this line outward to the depths. On the warmer days, focus your efforts shallower, knowing again that activity will be better from the middle to late part of the day, especially in the earlier part of the spring season. Proceed slowly with the bow-mount down, using your electronics as a key part of this fish-finding session. If you have side-imaging, make sure to use it as this technology is tailor-made for locating big schools of early season panfish.

As far as the spawning locations themselves, you’re looking for back bays, coves, and boat canals with warmer than main-lake water temperatures. That said, there will be zones within these warmer locations that fish congregate in more heavily. That can be docks, brushpiles, bulrushes, pencil-reeds, and lily pad root stems where only soft-bottom is available. Cover however is secondary to water temperature, so keep that in mind. Lastly, know that spawning location depth is relative for the lake you’re fishing and its clarity. Fish in clear water can spawn well outside of the reedbeds in 6FOW or more, while murky-water fish can be right up against the bank.

Spring Crappie Presentations – Speed Decisions

Now that you’ve found them, effort can go into catching them, but it’s good to pause a bit before you start slinging any old jig. Decipher an approach based on speed first and foremost, taking careful account of time of year and water temperature, along with time of day, and what you see on your electronics. If earlier, and fish are tightly schooled on pre-spawn transition flats and edges, you’ll want to fish slower than if it were later in the day, season, or otherwise warmer and fish are more spread out.

It’s hard to beat a bobber for crappies in that regard, as stationary targets presented in the right locations are hard for these fish to ignore, sometimes regardless of what bait or lure is tied on the business end of the line. Simple jigs and minnows early season under a slip bobber are deadly, and eventually give way to tubes and hair jigs both with and without minnows as fish slip into the spawn. Towards the tail end of the spring spawn and during warm afternoons, slowly retrieved jig and plastic combinations become the most efficient and effective means to cover water, catch fish, and target more aggressive crappies.

Push your way along slowly, from shallow to deep, knowing that your boat control can both cost and reap dividends depending how you drive. Especially in shallow water zones in that 2-4FOW range, any water clarity makes it imperative not to drive all over the areas you intend to fish. Start at the edges and pick your way in, making long casts to discover new pods of fish as you go.

Gear Up

The right line will play a role here, especially in heavy cover. Nanobraid varieties have found a niche in clear-water environments where long casts are the order of the day, and I can think of few better roles for that silky-slick line type than spring crappies. Especially in cover, fish fearlessly near brush and snags, knowing you can straighten out a hook if needed. Traditional monofilament still has a place, but do yourself a favor and re-spool with new line to avoid the annoyance of memory-laden line from last season.

Pairing up with the right rod will make even more of a difference, as most anglers fish for panfish with short, whippy rods in general. Varieties that extend 7’ or more cast small jigs and baits much further, especially when paired with light mono or nano-line varieties. With that much line out, it’s good to have a faster action rod than the noodle-type Ultra-lights so common for panfishing today. Faster actions get your hookset to the powerful part of the blank faster, meaning you’ll have to make the rod travel back less distance to impart a hookset, helping both to quicken up the hookset and keep big panfish buttoned-up in heavy cover.

Giving Back

With great knowledge comes a responsibility to the resource, such that ethically I’d have a dilemma in discussing spawning crappies without offering some advice as to the importance of selective harvest. When it comes to our panfish resources, overall size and quality fisheries are becoming more scarce than ever. As better educated anglers with more technology strive to catch more fish, only the most remote or otherwise out-of- the-way locations offer the consistent quality catches of yesteryear. That’s a trend supported statistically throughout every region of North America with panfish, and is a topic for concern amongst many fisheries managers.

The good news is that you can catch your panfish and eat them too if you follow some hard-won and evidence-based approaches to keeping spring crappies:

🔰 Selective Harvest – Late-ice congregations of panfish in the north, and shallow spawning bites nationwide represent intense periods of vulnerability. During these times, the biggest panfish in the system are easy targets and readily exposed.

🔰 Spread the Love – As anglers, we’re opportunists. It’s difficult to leave a lake that has a great bite for another, but keeping any number of fillets from 10 lakes is far better than that same number of fish from 1 lake. What I’ve found is that you can often find better fishing on nearby water bodies, distribute your take, and enjoy the hunt for new spots along the way.

🔰 Measure Everything – It’s hard to know what a big fish is without a good bump board. Get used to measuring your panfish and get a feel for what a good crappie really is where you live. Consider releasing fish over 11-12”es voluntarily, depending on the abundance and quality of the fishery you’re on.

🔰 Avoid High-Grading – Big crappies, especially in the north, are old fish and top performing individuals of their species. Keeping only the fittest members of any population leaves an unnecessarily shallow gene pool, a foul which is especially damaging to the increasingly few small, remote lakes where great panfishing can still be found. Tiny lakes simply can’t withstand the same pressure as larger ones, even from small numbers of anglers.

🔰 Fresh Only Please – Start with a plan as to how many fish you’d like to eat for an upcoming meal and stick to it. Freeze if you need to, but again, have a plan in the nearby future to consume them. Continual limit-fishing and freezer-filling far too often leads to freezer-burnt fish that are tossed out. Knowing what you want, catching that many, and throwing back the rest prevents those marathon cleaning sessions and promotes a sustainable catch and keep mentality.

🔰 Fish as a Treat – As far as the resource is concerned, gone are the days of serving nothing but bottomless baskets of fish. Round out any meal with some complimentary side dishes that don’t hide or cover up the main event, and you’ll find that the same fish go a lot further.

🔰 Do As I Say, AND as I do – Always remember that the younger generations are looking towards you and your behavior. Parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, make sure you pass along the right attitudes and make them healthy habits.

Keep it Fun

Chances are, you started your fishing career targeting panfish, fishing then very similarly to how you are now for these same fish. It’s a great time of year to bring kids or people without much fishing experience out on the lake to enjoy one of the best bites of the year. For you walleye and bass anglers, don’t hesitate to switch over to some shallow crappies early season if your other bites head south, to remember what got you excited about fishing in the first place.

Mastering the Mouse Retrieve

Written by Charlie Robinton

Looking to catch big fish? Maybe it's time to use a big fly! Mouse-patterned retrieves are designed to resemble live mice and attract larger fish looking for a bigger meal! But it's not just about casting the mouse and waiting - you need to have the mouse simulate what the real thing would look like in the water. It's not just a fly - it's a proven technique to catch yourself some big trout!

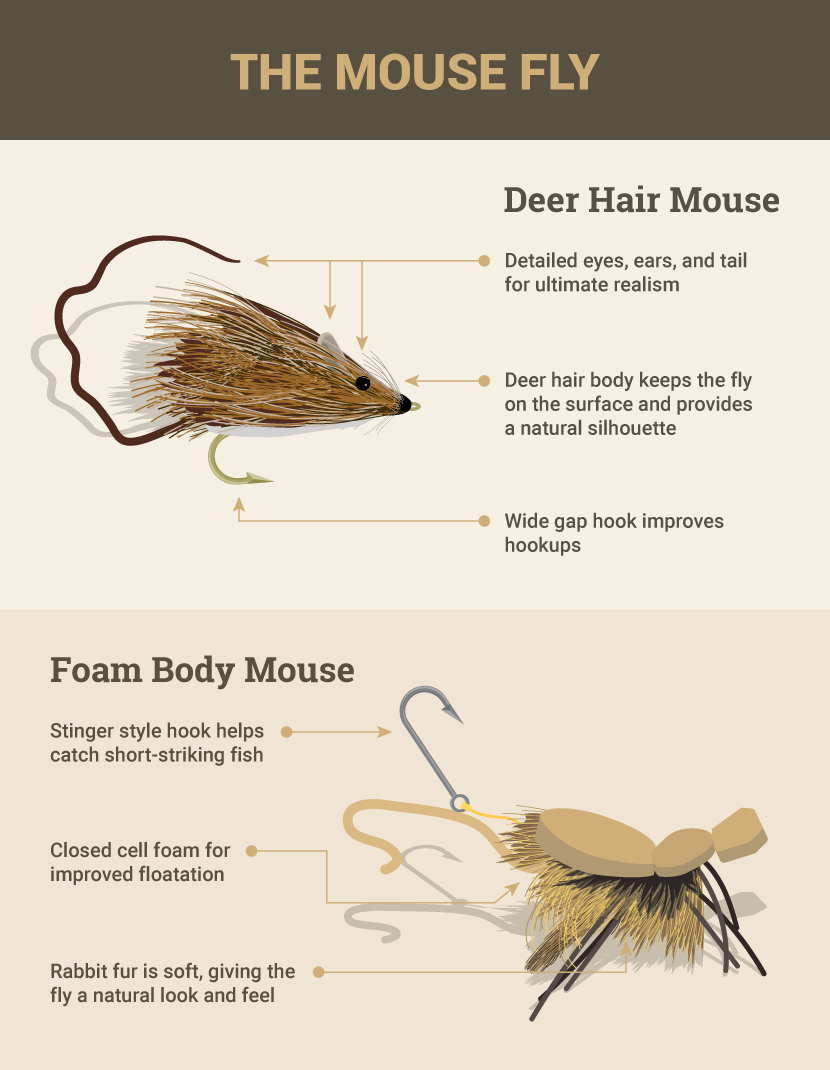

Mouse-pattern flies are meant to look like a small field mouse and behave like one in the water. A typical mouse fly designed for trout fishing will be 2-3 inches long and tied on a size 2-6 wide-gap hook. Mouse flies are most often tan, brown, or grey, just like the real thing. Many materials can be used to create mouse-pattern flies, but the most realistic flies are tied using deer hair because of its buoyancy and natural appearance. Keep in mind that mouse flies are meant to ride high on the surface of the water, so your pattern of choice should feature deer hair, foam, or other buoyant materials to help it float.

Many fly shops carry at least one mouse-pattern fly, but these flies are often designed for bass fishing and have a heavy monofilament weed guard looped over the hook to protect it from snags. This feature is helpful if you are fishing in weedy or brushy areas, but it is unnecessary for trout fishing and can hamper your ability to hook fish. You can easily remove the weed guard by cutting it off with nippers.

Even large trout have relatively small mouths for their body size, so hooking them on such a bulky fly can be a challenge. To get better hookups, some anglers have started tying their mouse flies with stinger hooks positioned farther back on the fly, toward the end of the tail. If you are getting strikes but having trouble connecting with fish, a stinger hook fly may be the answer.

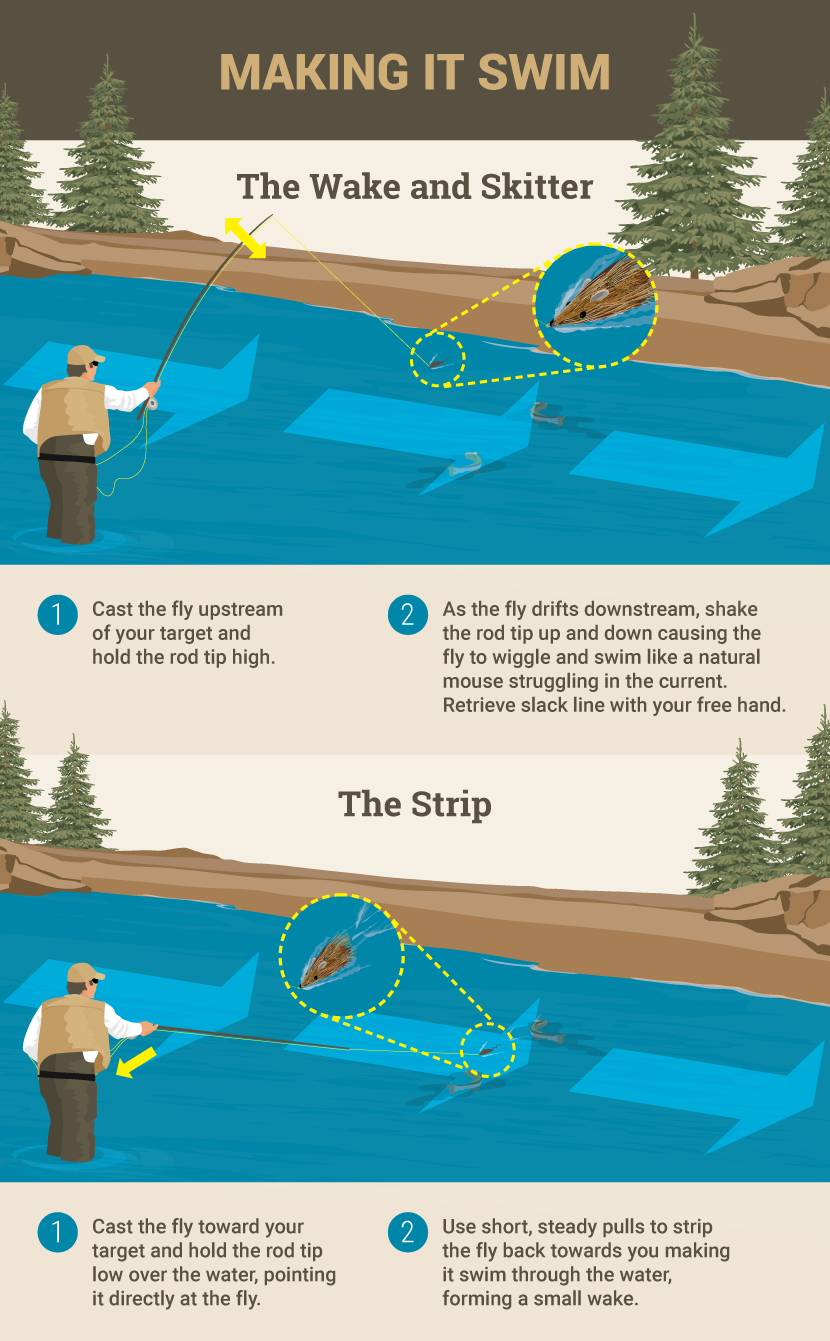

There are two general ways that mouse flies are fished. They can be "waked" or "skittered" using the rod tip, or "stripped" by pulling in the line by hand. Both techniques are effective and have their place in the mouse angler's bag of tricks.

The Wake and Skitter

Waking a mouse fly is most effective when there is a steady current. In most cases, you will want to position yourself across from your target and place your cast upstream. Make a quick mend when the fly hits the water to remove any drag that might pull the fly away from your target, then raise your rod tip to remove slack line from the water and create a direct connection to the fly. Twitch the rod tip as the fly comes toward you while slowly retrieving the slack with your free hand. This will make the fly look as if it is swimming and struggling in the current.

This method can also be used to fish in a downstream direction to wake the fly on a tight line. Cast the fly across or slightly downstream, make a quick mend to reduce unwanted drag, then allow the fly to swing slowly across the current, generating a sizeable wake behind it. Follow the fly with your rod tip to keep it swimming at a steady pace. You can experiment with raising the rod and imparting the twitching action with this retrieve as well.

The Strip

In areas with little or no current, you will need to change your approach to get the fly to swim properly. Cast beyond your target and allow the fly to settle. If there is some current, you may want to make a mend so that the fly is not pulled away from the strike zone. Keep the rod tip low and point it at the fly, then retrieve the line in very short, steady strips with your free hand.

Emulate a mouse

Try to imagine how a mouse would look while swimming. Mice do not pop and splash their way through the water like an Olympic swimmer doing the butterfly. They plod along treading water with their head slightly above the surface and their body submerged. Imitate this slow, steady swimming action with your retrieve and you will attract the big fish.

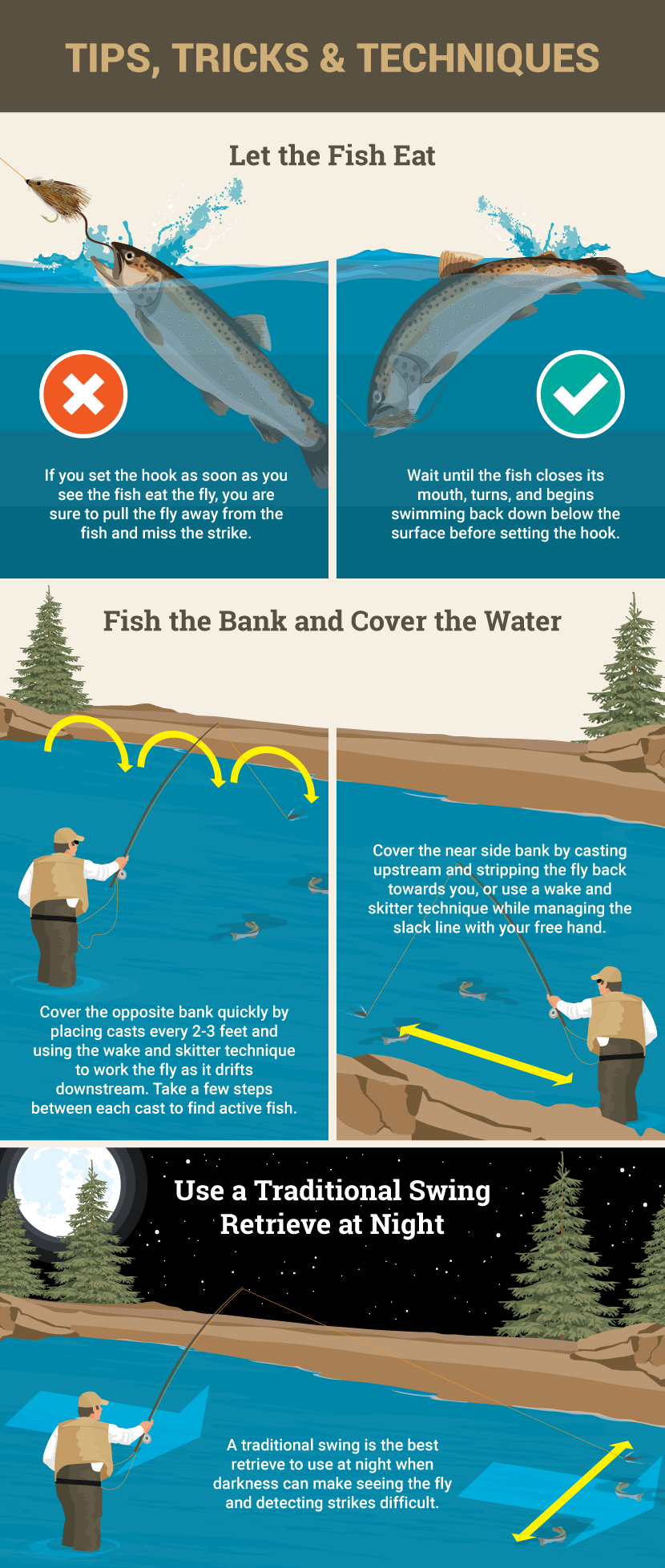

Let the Fish Eat

When a big trout rockets out from beneath an undercut bank and smashes your mouse fly, your first instinct might be to jerk on the rod, but you will be pulling the fly right out of the fish's mouth. Try to stay relaxed here! Allow the fish time to close its mouth and turn with the fly before setting the hook. Simply watching the fish eat and turn can be helpful for some, but if you are having trouble keeping it together, try counting "one, one thousand" before slamming the hook home.

Fish the Bank

Mouse flies work in a variety of water, but it makes sense that presenting the fly where trout are most likely to see the actual critter will get you more strikes. Mice, voles, and other rodents end up taking a dunk more often than you may think, but when they do it is usually because they fell from the bank. When they end up in the water, their first instinct is to escape danger by swimming as fast as possible back toward shore. By presenting your fly as close to the bank as possible and doing your best to keep it there, you are offering the most natural presentation to the fish. You can accomplish this either by making short, quick presentations to the opposite shore while wading, or casting upstream and using the wake and skitter technique to swim the fly back toward you along the near bank.

Keep an eye out for steep banks with plenty of structure and depth, undercuts, and grassy shorelines, as all will have the potential to be good mouse fishing spots.

Cover the Water

Whenever fishing large flies with an active retrieve, it makes sense to cover the water quickly rather than saturate an area with multiple casts. Trout have acute senses and they are sure to immediately notice a giant mouse struggling across their dining room table. You are searching for an aggressive reaction from a predator, and not all trout will be in the mood to react at all times. Keep moving and cover the water methodically by placing a cast every few feet, paying extra attention to any obvious structures and fishy looking lies. This way you will place your fly in front of more fish and increase your odds of finding one that is in the mood.

Try Fishing at Night

Where it is legal, nighttime mouse fishing can be a real adrenaline rush. Do some daytime recon on your favorite river to determine some good areas that will be safe to approach at night, then return well after dark with a mouse fly attached to some heavy tippet.

Nighttime fishing introduces an obvious challenge. The darkness will make it harder to wade, cast, and detect a strike. Try to use just your flashlight on the trail as you approach the river, and turn it off well before you reach the water. This will allow your eyes time to adjust to the low light.

In areas with some current, a wake or swing retrieve on a tight line can be the best approach at night. Start at the top of the hole and work methodically, moving a couple of steps in between casts. With the line tight from downstream water tension on the fly, you will feel the weight of the fish when it strikes.

If there is little or no current, you will need to tune in with your senses to detect a strike. Try to focus your vision on the general area where your fly is and pay attention to any unnatural movement. Get in tune with the rhythmic sound of the river and listen for any splash or swirl that is out of sync. This could signify a fish has come up to take a swipe at your fly.

You will hook more fish if you are patient and don't set the hook until you feel the weight of the fish. This can be hard to do when you can barely see and your adrenaline is racing, but you will be rewarded with more big fish in the long run.